La Giudecca is a district of Bova that was inhabited by a Jewish community between the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th century. Almost completely forgotten, this striking section of urban space has been included in part of the Gerhard Rohlfs Museum of the Calabrian Greek Language and has been enhanced by a contemporary art installation by the artist Antonio Puija Veneziano. |

|

The first evidence of the presence of a Jewish community in Bova dates back to the late 15th century. In fact, we know that in 1502, the Court of Naples complained of not having collected taxes that the Giudecca of Bova owed to the treasury as early as 1497. Subsequently, on 23rd August 1503, the six households which made up the Jewish community there paid, through Antonio Carnati, 9 ducats as part of the fiscal taxes imposed on the Jews of the Kingdom of Naples. Six households also registered in 1508, when the Jews from Bova asked the authorities to settle their taxes in instalments, a clear sign of possible economic difficulties. |

|

The Jewish settlement in Bova could date back to the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492.That year a number of Sicilian Jews moved to Reggio and two years later there were groups throughout the district. The second edict of Ferdinand the Catholic (1511) which decreed the expulsion of Jews from the Kingdom of Naples led to the abandonment of Bova’s Jewish community. In that same year, the local authorities asked for their cancellation from the tax roll. Despite this, a Bovese report, written in 1774 by the scholar Domenico Alagna, recalls that the Jews were expelled from Bova only in 1577, with the accusation of having spread the plague. |

|

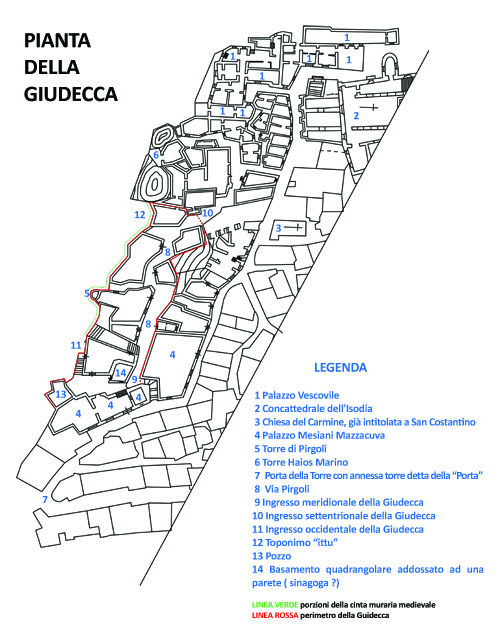

It is Domenico Alagna who provides us with detailed information on the location of the Giudecca of Bova, which was on the outskirts of the city, in the Pirgoli district (from the Greek “towers”) located between two doors that opened respectively to the south, near Torre della Porta, and to the north near the Aghios Marini Tower. |

|

La disamina della fonte storica è la tematica prescelta dall’artista, immortalata sulla ceramica mediante la struttura a spirale delle iscrizioni che induce il fruitore dell’opera a prestare attenzione al testo, soffermandosi sull’interpretazione e il significato della scrittura stessa, così come fa lo storico di fronte alle carte d’archivio. |

|

Antonio Pujia Veneziano has created an art installation by developing a series of glazed and engraved ceramics under the title “Pirgos talking pottery” around which are fragments of information about the Jews of Bova from between the end of the 15th and beginning of the 16th centuries, as well as a chronicle of Bova from the eighteenth century.

Le iscrizioni trascritte sulle ceramiche, secondo la grafia del XVIII secolo, riportano le parole che il bovese Domenico Alagna fece confluire nell’opera dell’erudito, Cesare Orlandi, “Delle Città d'Italia e sue Isole adiacenti”, edita a Perugia tra il 1770 e il 1778. Ai cinque tondi l’artista ha aggiunto un altro disco, incastonato sulla parete adiacente l’ingresso secondario di Palazzo Mesiani, costruito alla fine del XVIII secolo sul sito dove era in precedenza insediata la giudecca di Bova. Il soggetto è un particolare della planimetria urbana del quartiere ebraico di Pirgoli raffigurato con l’intento di esaltare la percezione di uno spazio fisico quasi dimenticato, ma un tempo abitato da genti di religione ebraica. |

|

The inscriptions on the ceramics, transcribed according to 18th century orthography, show the words that Domenica Alagna of Bova sourced from the work of the scholar Cesare Orlandi “On Italian Cities and its Islands”, published in Perugia between 1770 and 1778. The artist added another disc to the five ceramic rounds set on the wall adjacent to the side entrance of Palazzo Mesiani. This building was built at the end of the 18th century on the site where Bova’s Jewish neighbourhood had previously been located. The piece is a detail of the urban plan of the Jewish quarter of Pirgoli displayed with the aim of enhancing the awareness of an almost forgotten physical space, once inhabited by Jewish people. |

|

Symbols and imprints of ancient rituals, made of ceramic and arranged along the walls of the Giudecca, are the result of a unique participatory workshop that Pujia curated by directly involving the children of Bova. The Menorah, the pomegranate and the knot of Soloman evoke a piece of Jewish culture in the continuous centuries-old history of Bova. This is evidenced in a letter of thanks translated from Hebrew, from the that Rabbi Shaul Robinson of the Lincoln Square Synagogue in Manhattan New York (USA) sent on June 8, 2018 thanking the municipal administration of Bova for the redevelopment works of this small Giudecca in southern Italy. |

|

|

|

|